Joel Norcross, Emily's grandfather, dies.

May 5, 1846

Joel Norcross, Emily Dickinson's grandfather died on 5 May, 1846. As some scholars suggest, it is the occasion of his death that prompted the series of events, which lead to Emily Dickinson's iconic daguerreotype.

A year after Joel Norcross' death, his daughter Emily Norcross who was still deep in mourning wanted an image of him. During this time, daguerrian artist William C. North was taking daguerreotypes of the people of Amherst. To appease his wife, Edward Dickinson hired North to have Joel Norcross' daguerreotype taken.

A year after Joel Norcross' death, his daughter Emily Norcross who was still deep in mourning wanted an image of him. During this time, daguerrian artist William C. North was taking daguerreotypes of the people of Amherst. To appease his wife, Edward Dickinson hired North to have Joel Norcross' daguerreotype taken.

According to Mary Elizabeth Kromer Bernhard, it was also during this occasion that Emily Dickinson and her mother Emily Norcross also had their daguerreotypes taken by the same artist.

On 25 August 1846 when she was only fifteen years old, Emily made her first alone trip to Boston for health reasons. The trip made a big impression on Emily, especially her visit to the Mount Auburn Garden Cemetery.

As Emily wrote in a letter to Abiah Root:

"Father & Mother thought a journey would be of service to me & accordingly, I left for Boston week before last. I had a delightful ride in the cars & am now quietly settled down, if there can be such a state in the city. I am visiting my aunt's family & am happy . . . I have been to Mount Auburn, to the Chinese Museum, to Bunker hill. I have attended 2 concerts, & 1 Horticultural exhibition. I have been upon the top of the State house & almost everywhere that you can imagine. Have you ever been to Mount Auburn? If not you can form but slight conception - of the "City of the dead.

Sits for a daguerreotype

Dec 10, 1846 - Mar 1847

Emily Dickinson and her mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson, were believed to have sat for daguerreotypist William C. North sometime between 10 December 1846 and March 1847 to have their daguerreotypes taken.

The result was a sixth-plate daguerreotype, showing a three-quarter view of the poet seated with her arm resting on a cloth-covered table with a book, possibly the Bible, while gripping a small bouquet of flowers and looking directly at its observers.

This iconographic photograph, which presents the Emily Dickinson in black and white, is believed to be only known photograph of the poet for years, before Dr. Philip F. Gura acquired what is alleged to be a second photo of Dickinson on 12 April 2000 in an ebay auction.

Emily graduates from Amherst Academy

By August 1847, Emily graduated from Amherst Academy. After graduation, she began preparing for Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, which at that time was one of the best boarding schools in New England.

Emily spent hours in her room preparing for her admittance exam, studying mathematics, ecclesiastical history, geometry, and science. Her father was an ardent believer in the benefit of a girls' boarding school experience, even if it meant his favorite daughter would spent much of the next year away from home.

Enters Mount Holyoke

In the fall of 1847, Emily and her father traveled to Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. After the exhausting three-day entrance exam, Emily began attending the school on 30 September 1847 where she was assigned by the headmistress, Mary Lyon, to room with her cousin, Emily Lavinia Norcross.

According to her letters, her day was plotted out with almost military precision. When the girls were not in classes, they were often completing chores. Each boarder paid only sixty dollars a year in tuition, paying for the rest of her board with domestic labor. Emily was assigned to polish silver.

During this time, older brother Austin, visited her often with gifts and sweets from home. As time passed, Emily's homesickness dissipated. She grew to enjoy the routine of school, the stimulation of her studies, and the friendships she made.

Writes to a friend regarding her illness

May 16, 1848

During her first year at Mount Holyoke, Emily became sick and developed a cough, which she might have contracted from her cousin and roommate, Emily Lavinia Norcross who was suffering from Tuberculosis at the time. On 16 May 1848, she vented her frustrations regarding her illness and her failed attempts at hiding her health conditions from her parents in a letter to Abiah Root where she writes:

"I had not been very well all winter, but had not written home about it, lest the folks should take me home. During the week following examinations, a friend from Amherst came over and spent a week with me, and when that friend returned home, father and mother were duly notified of the state of my health. Have you so treacherous a friend?"

"Now knowing that I was to be reported at home, you can imagine my amazement and consternation when Saturday of the same week Austin arrived in full sail, with orders from head-quarters to bring me home at all events. At first I had recourse to words, and a desperate battle with those weapons was waged for a few moments, between my Sophomore brother and myself. Finding words of no avail, I next resorted to tears . . . As you can imagine, Austin was victorious, and poor, defeated I was led off in triumph."

Returns home from Mount Holyoke

August 1848

Upon learning of her health conditions, Emily’s father sent for her immediately and insisted that she return home at once. She returned home, and after resting at home for a few weeks Emily did finish her term at Mount Holyoke.

However, by August 1848, Emily was back at Homestead, never to return again to Holyoke. Some speculate that she refused to sign an oath given the headmistress, Mary Lyon, which stated she would devote her life to Jesus Christ. Lyon was a religious woman who hoped that many of her pupils would become missionaries and travel to distant lands to convert people to Christianity. Rrealizing she no longer wanted to attend there, went home and never returned. Nonetheless, her departure from Holyoke marked the end of her formal schooling.

Back at home, Emily’s health improved. And despite her later reputation as a recluse, she regularly attended parties and usually found herself the center of a group of people who were dazzled by her intelligence and wit. She often kept her friends laughing for hours on end and even outraged her parents by pulling pranks such as leaving the funeral of a family friend with her wild cousin Willie in his fast horse and buggy. Dickinson's father was deeply angered by this breach of propriety.

Lavinia leaves for Ipswich Female Seminary

In 1849, Emily's sister Lavinia left home for Ipswich Female Seminary, leaving Emily with many of the household chores. The change was hardly welcome. She disliked the domestic chores and grew frustrated with the time constraints it imposed on her. As she exclaimed in a letter to Abiah Root in 1850, "God keep me from what they call households." She continues, "The circumstances under which I write you this morning are at once glorious, afflicting, and beneficial. . . . On the lounge asleep, lies my sick mother . . . here is the affliction. I need not draw the beneficial inference--the good I myself derive, the winning the spirit of patience, the genial house-keeping influence stealing over my mind, and soul, you know all these things I would say, and will seem to suppose they are written, when indeed they are only thought."

"Magnum bonum" is published

On 7 February 1850, a poem similar to the first line of Emily's Valentine letter to George H. Gould was published anonymously in "The Indicator", a student magazine of Amherst College. One of the writers in the publication was Gould, a friend of Austin that acted as a likely consignee for Emily.

The first line of the poem, and the letter, is one crackling "nonsense" which goes: "Magnum bonum, "harum scarum," zounds et zounds, et war alarum, man reformam, life perfectum, mundum changum, all things flarum?" The poem, stands to be Emily's first published work during her lifetime.

The Great Revival and religious imagery

August 11, 1850

When Emily turned twenty in 1850, a religious movement called The Great Revival was taking place. A fervent renewal of Christian spirituality, the Revival inspired huge numbers of people to officially join churches and declare themselves "for Christ." It also resulted in the Temperance Movement, which argued for banning the consumption of alcohol.

In Amherst, a number of town saloons were forced to close. Dickinson's father joined the Temperance Movement and even officially joined his Congregational Church on August 11, 1850, publicly declaring his faith. Emily, still unconvinced and unsure, did not. Thinking about the Congregationalist faith, she could not accept all of its tenets, and its concepts of judgment and hell frightened her.

In Amherst, a number of town saloons were forced to close. Dickinson's father joined the Temperance Movement and even officially joined his Congregational Church on August 11, 1850, publicly declaring his faith. Emily, still unconvinced and unsure, did not. Thinking about the Congregationalist faith, she could not accept all of its tenets, and its concepts of judgment and hell frightened her.

She gave religious matters her thorough attention and as a result, religious imagery found its way into her poems, which she was writing with more frequency now. She wrote about faith, domestic matters, nature, immortality and, increasingly, death. She was becoming preoccupied with death and the soul, and her own spiritual investigations gave her a deep well of imagery and metaphor for her poems.

Emily's friend, Leonard Humphrey, dies

In November 30, 1850, Leonard Humphrey, Emily's friend and tutor, died of what was then called brain congestion. Humphrey was a very dear friend to Emily. She deeply admired him, first as her principal at Amherst Academy and later as a friend and mentor.

For Emily, Humphrey's death was a crushing blow. Thus, she spent the next few months in a depression. However, as Emily wrote in a letter to Thomas Higginson more than ten years later in 1862, Humphrey's death (as well as that of her second tutor Ben Franklin three years later) continues to affect her and her writing for years to come.

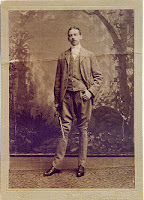

Austin graduates from Amherst College

June 7, 1851

Emily's brother, Austin, graduated from Amherst College on June 7, 1851. After graduating from Amherst, he began teaching at a boy's school in Boston.

During this time, Emily was already writing poems in her room, but did not tell anyone about her budding craft, nor her literary experimentation with structure and style, such as assonant rhyming patterns and dashes dividing lines into rhythmic sections.

During this time, Emily was already writing poems in her room, but did not tell anyone about her budding craft, nor her literary experimentation with structure and style, such as assonant rhyming patterns and dashes dividing lines into rhythmic sections.

She also spent almost as much time reading as she did writing. She devoured the poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and constantly read "The Atlantic Monthly," "Harper's," and "Scribners." She also read novels like Vanity Fair by Thackeray. She especially loved the novelists George Eliot and Thomas Carlyle.

"Sic transit" is published

Feb 14, 1852 - Feb 20, 1852

Emily enjoyed sending her short poems to friends to mark holidays and other special occasions. On Valentine's Day 1852, she wrote a poem beginning with "Sic transit" and sent it as a Valentine to William Howland, one of the young men in her father's law office. Little is known about William Howland, but it is unlikely that he and Dickinson ever had relationship.

Howland was so impressed by Dickinson's poem that he sent it, without telling her, to the Springfield Republican newspaper. A few days later on 20 February, while she was leafing through the newspaper, Dickinson caught sight of the poem printed on one of the pages of the Springfield Republican. She was mortified and successfully hid the newspaper from her father.

Emily's dear friend, Benjamin Franklin Newton dies

Mar 24, 1853

In March of 1853, Dickinson was flipping through the Springfield Republican and came across a tiny obituary. She read that her dear friend and second tutor Benjamin Newton had died of tuberculosis on March 1853. Dickinson fell ill almost at once, deeply shaken by her friend's sudden death.

.

Although Newton had become sick ever since he left Amherst, his death still came as a shock for Emily. His counsel and thoughtful advice about Emily's poems had buoyed her spirits, which had just started to take flight. Newton's death affected Emily for months. And she would remember him for years to come. Taking place just a few years after the death of her first tutor, Leonard Humphrey, his death was another crushing blow for her.

However, Newton's impact on Emily's life did not end with his death, because Newton's Transcendental philosophies will resonate in Emily's poems - both in subject and in style - for years to come.

Emily travels to Washington

Feb 1855 - Mar 1855

In 1855 Emily travelled to Washington, spending three weeks there with her father, mother, and sister. Emily had a long-standing interest in politics and always kept abreast of current events. Even though she had been unwilling to leave Amherst, she adored Washington. She and her family rode a boat down the Potomac River, visited Mount Vernon and the Capitol, and attended numerous Washington parties.

It was at these gatherings that the shy poet shined. Dickinson dazzled her father's political cohorts. Her insights into world affairs and her dry sense of humor bewitched almost everyone who met her at these functions. Roger Taney, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was especially enchanted by Dickinson. The Dred Scott case was hanging over his head; he had spent most of the evening discussing it, and found Dickinson's wit refreshing.

It was at these gatherings that the shy poet shined. Dickinson dazzled her father's political cohorts. Her insights into world affairs and her dry sense of humor bewitched almost everyone who met her at these functions. Roger Taney, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was especially enchanted by Dickinson. The Dred Scott case was hanging over his head; he had spent most of the evening discussing it, and found Dickinson's wit refreshing.

While in Washington, Emily ran into one of her childhood friends, Helen Fiske, and Fiske's husband, a soldier named Edward Bissell Hunt. Emily found Hunt captivating, and Hunt was fascinated by Dickinson. Some scholars have said that Dickinson fell in love with Edward Hunt, although there is no evidence to back up this claim. However, Emily did write in a letter at the time that Edward Hunt intrigued her more than any man she had met before.

Meets Reverend Charles Wadsworth in Philadelphia

Mar 4, 1855

After three weeks in Washington, Emily traveled to Philadelphia to visit with her old school friend Eliza Coleman. Eliza's father, Reverend Lyman Coleman, was pastor of the Presbyterian Academy of Philadelphia, and through him Dickinson made the acquaintance of a serious, dark-eyed man named Dr. Charles Wadsworth.

Wadsworth was a preacher at Arch Street Presbyterian Church. He was a brilliant man, and Dickinson felt immediately drawn to him. He was married, but he took to Dickinson immediately and when she left, they began a long correspondence. Wadsworth occasionally visited Dickinson in Amherst. Dickinson turned away more and more visitors as the years passed, including her good friend Samuel Bowles, but she never turned away Dr. Charles Wadsworth.

Wadsworth was a preacher at Arch Street Presbyterian Church. He was a brilliant man, and Dickinson felt immediately drawn to him. He was married, but he took to Dickinson immediately and when she left, they began a long correspondence. Wadsworth occasionally visited Dickinson in Amherst. Dickinson turned away more and more visitors as the years passed, including her good friend Samuel Bowles, but she never turned away Dr. Charles Wadsworth.

This trip to Washington proved that Emily had both the social and the intellectual gifts to be part of that world. However, after returning home from her trips to Washington (and subsequently Philadelphia), she retreated for good into her cloistered, self-made world. Three portraits hung on the walls of her room: George Eliot, Thomas Carlyle and Dr. Charles Wadsworth.

Edward Dickinson repurchases Homestead

In November 1855, following the death of David Mack, Edward Dickinson re-purchased his father's Homestead and moved his family there. However, although Emily enjoyed the extensive gardens and the conservatory her father built for her, the move back to the old house was deemed a struggle by Emily who has lived most of her formative years in West Street. As she writes in a letter to Mrs. Holland,

"I cannot tell you how we moved. ... I supposed we were going to make a "transit," as heavenly bodies did-but we came budget by budget, as our fellows do, till we fulfilled the pantomime contained in the word "moved." It is a kind of gone-to-Kansas feeling, and if I sat in a long wagon, with my family tied behind, I should suppose without doubt I was a party of emigrants!"

Austin and Susan Gilbert marry

July 1, 1856

In 1853, Austin began courting one of Emily's friends, Susan Gilbert. Susan and Austin had met at the Sewing Society and they deeply admired each other. Austin thought Susan pretty and graceful and intelligent, and Susan found Emily exceptionally witty and articulate. The whole Dickinson family, in fact, took to Susan immediately. They were engaged during Thanksgiving on 23 March 1853 at the Revere Hotel in Boston. And on 1 July 1856, the couple married in the home of Susan's aunt Sophia Arms Van Vranken in Geneva , New York. They then moved to the Evergreens, next door to the Homestead.

In 1853, Austin began courting one of Emily's friends, Susan Gilbert. Susan and Austin had met at the Sewing Society and they deeply admired each other. Austin thought Susan pretty and graceful and intelligent, and Susan found Emily exceptionally witty and articulate. The whole Dickinson family, in fact, took to Susan immediately. They were engaged during Thanksgiving on 23 March 1853 at the Revere Hotel in Boston. And on 1 July 1856, the couple married in the home of Susan's aunt Sophia Arms Van Vranken in Geneva , New York. They then moved to the Evergreens, next door to the Homestead.

Emily and Sue's friendship, which had continued uninterrupted since they were children, strengthened after Sue's marriage into the family. The marriage brought a new "sister" into the family, one with whom Emily felt she had much in common. That Gilbert's intensity was finally of a different order Dickinson learned over time, but in the early 1850s, as her relationship with Austin was waning, her relationship with Gilbert was growing. Gilbert would figure powerfully in Dickinson's life as a beloved comrade, critic, and alter ego.

Supposed writing of the Master Letters

Believed to be written between 1858 to 1861, the three letters, which Emily Dickinson drafted to a man she called "Master," stands at the heart of Emily's mysterious life.Although there is no evidence the letters were ever posted, they indicate a long-distance relationship, where correspondence is the primary means of communication. Given that Emily Dickinson did not write letters as a fictional genre, it is supposed that these three letters were part of a much larger correspondence yet unknown. As to the identity of "Master", some biographers have been convinced Dickinson might have been romantically involved with the newspaper publisher Samuel Bowles, a friend of her father's, Judge Otis Lord, or a minister named Charles Wadsworth. A relatively recent theory has emerged that proposes William S. Clark, a prominent figure in Amherst at the time, as the identity of her "Master".Based on Jay Leyda's dating, the letters were probably written as follows: early spring 1858 ("I am ill"), January? 1861 ("If you saw a bullet"), and February? 1861 ("Oh! did I offend it")

"Nobody knows this little rose" is published

Aug 2, 1858

On 2 August 1858, Emily's poem beginning with "Nobody knows this little rose" is printed anonymously in the Springfield Daily Republican. The Republican's editor, Samuel Bowles is said to be directly responsible for its printing.

Wadsworth visits Emily in Amherst

Charles Wadsworth became an important figure in Emily's interior universe, serving as her muse. Emily secretly sent letters to him through friends, asking them to write his address on the envelope in their handwriting.

In early spring of 1860, Emily was surprised to find Wadsworth at the door. He had come for an unexpected visit to Amherst, and Emily joined him for a carriage ride. Emily's niece Martha Dickinson Bianchi-Austin and Sue's daughter-later said that when Emily went for the carriage ride, Lavinia rushed across the lawn into Sue's house and said breathlessly: "I am afraid Emily will go away with him." The couple returned, however, and Lavinia returned to the house to find Wadsworth gone and Dickinson locked in her room.

Begins the habit of dressing in white

In 1861, Emily adopted the habit of dressing exclusively in white, a habit she kept until her death 24 years later. During the same year, she also Emily begged her cousins to take her place at a commencement tea at home for Amherst College students because she felt, "too hopeless and scared" to face visitors. Eventually she secluded herself behind her doors altogether until, for the last fifteen years of her life, no one saw her but her immediate family.

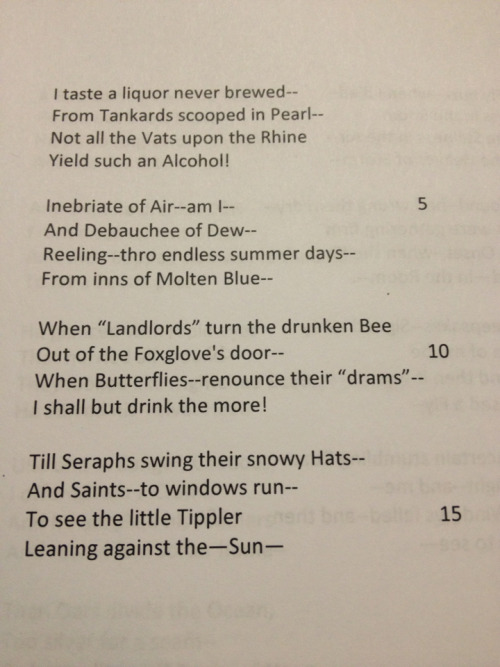

“I taste a liquor never brewed" is published

May 4, 1861 - May 11, 1861

On May 4, 1861, one of Dickinson's poems, "I taste a liquor never brewed," appeared in Samuel Bowles' Springfield Republican under the title "The May-Wine". Like all her poems published during her lifetime, the poem was unsigned, but it pleased Emily to see her words in print, nonetheless.

Emily's nephew, Edward, is born

Jun 19, 1861

Austin and Susan Dickinson’s first child, Edward, is born 19 June 1861.